True Crime

Solo Ehibiton

Screw Gallery, Leeds

November 4th - 20th 2022

Curated by Allan Gardner

Screw Gallery, Leeds

November 4th - 20th 2022

Curated by Allan Gardner

Accompanying publication available here.

True Crime and Real Pain: Maggie Dunlap’s Dead Girl Industrial Complex

Exhbition text by Allan Gardner

In 2014 I had an office job where I managed social media accounts and wrote copy for an estate agent in Aberdeen, Scotland. The job was underpaid but okay overall, mercifully allowing me to work with headphones which sounded great at first but very quickly caused me to develop a hatred for almost every form of music I could think of. Eventually I started just listening to podcasts instead, finding my spike in headphone-time coming almost in unison with the first episodes of Serial - the series often cited as bringing the boom in True Crime media into the mainstream. In spite of the show’s enormous popularity, listening to descriptions of graphic violence whilst tapping away at a corporate Facebook account in an identikit office felt surreal, especially when the genre’s enormous popularity meant that shows like Casefile - with a significantly darker, less journalistic approach, found their way onto the apple podcast charts. Something that should have felt deviant - listening to graphic depictions of murder, sexual violence, kidnapping and torture - could no longer, millions of people worldwide were doing the same thing. As the phenomenon has grown, an interest in True Crime media has entirely transcended subculture. Viewers have no further interest in transgressive or violent media beyond the genre, maintaining entirely mainstream media diets - the very real murders becoming just another piece of reality television.

At the time of writing, True Crime is the most popular genre in global podcasting, Monster: The Jeffrey Dahmer Story is the most popular show on Netflix and Oxygen True Crime (a rebrand from Oxygen Network in 2019) is attracting 300k viewers a week. The international fascination with True Crime - most often real violence, real trauma, real death and real victims - is undeniable. Worth noting in all of this is that although (in the US) men are significantly more likely to be murdered, according to FBI data, 70% of serial murder victims are women. The vast majority of True Crime media places women in the role of the victim, often with a heavily implied or explicitly spoken element of sexual violence.

The top three True Crime podcasts (Oct ‘22) are Crime Junkie, My Favourite Murder and Morbid - sitting at number 2, 4 and 10 respectively - are all hosted by women. This is a cottage industry of women selling repackaged female horror back to women, described by Maggie Dunlap as The Dead Girl Industrial Complex. Although somewhat tongue-in-cheek, this descriptor is an effective means of reconciling the very real horror depicted in True Crime media with the generic cuts, pacing and narrative reveals of reality tv that have come to typify it. The structure of long running genre staples like Unsolved Mysteries has a firmly demarcated shift with the most recent Netflix episodes of the show having more in common with Drag Race or Bake Off than a document of grizzly murder.

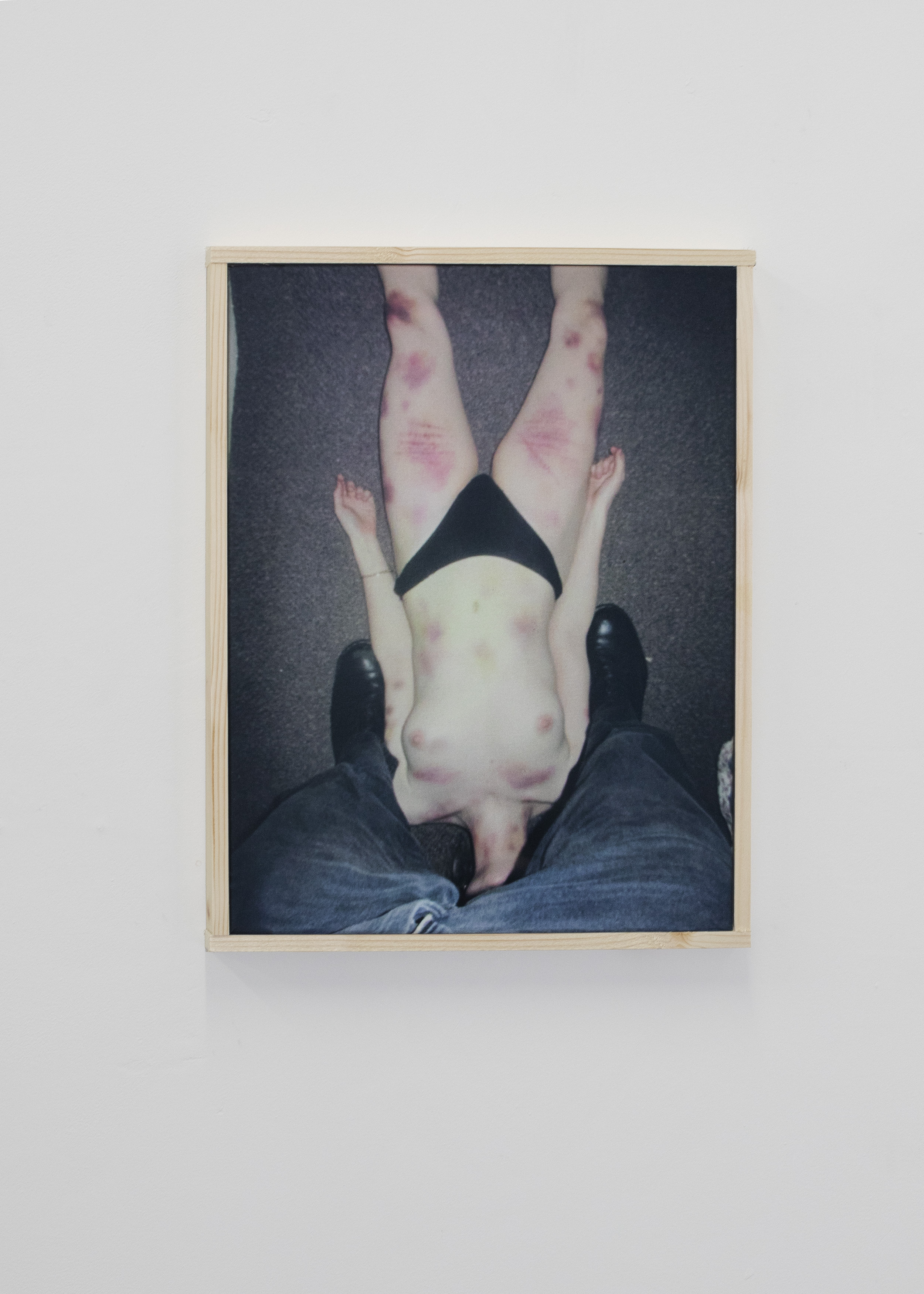

new body of work removes the narrative structure completely, ripping away the warm blanket of familiar media aesthetics and laying bare cold, blue flesh. It provides nowhere for the viewer to hide, placing them incontravenably in the path of the reality of the image. There is no story, no clues, no friends and family in talking heads to cast doubt on police investigation and no chirpy hosts to lighten up the whole ordeal. There isn't even a salacious description of the violence inflicted - there are only bodies.

The body is an essential device in these works, whether in reclining Venus, curled in an off-angled foetal position or splayed childlike and rigid, Dunlap's anonymous victims are given nothing beyond the body. Flesh, marked or discoloured, is used with the express purpose of conveying the unnamed potential of harm - these photographs offhandedly depict a record of pain, harm and horror that goes beyond a signal for empathy and enters the truly abject. There is nothing there except the body, and like all bodies, these are temporary and futile.

the literal body could be regarded as a sort of ramping up, a phrase often used in connection with serial killers moving on from fantasy to reality (or non-human animals to humans), whereby the viewer desires more than just the description of violence or the pain of those close to the victim and instead feels a need to see what is described. Networks like Oxygen aren't going to show you the real, dead bodies of victims and My Favourite Murder aren't going to drop a link in the description to download the crime scene photography but this is not a moral issue - the same morality would suggest we not make entertainment our of horrific violence at all, probably barely distinguishing between visual and described. The reason that this sort of imagery isn't omnipresent in True Crime media is a simple one: Viewers don't want to see it.

recipe dictates that we focus on the ephemera and not the act, perhaps describing the first murder of a serial killer in more detail and by the last the victim becomes just another murdered girl and this is not an accident, they are not forgetting where they left the wrench (so to speak) and instead are trying to avoid trauma-fatigue in their viewers. Depictions of real violence create real discomfort, they turn real stomachs, make us aware of our own mortality and potential for pain and so we rely instead on smash cuts and teary-talking heads, basking in the warm waters of love and empathy for the victim, pretending we're not here to be entertained by their pain and the pain of those around them. Indeed, the less visually explicit version of the genre is far more disturbing, creating a sort of media-diet predicated on consuming the traumatic memories of those close to the victim far more than the actual incidents of horrific violence.

Dunlap's works remove the facade, refusing to provide context or narrative, stripping back the genre beyond entertainment and purely into the abject. They ask the viewer how entertained they truly are when confronted with the body in the woods, no smash cuts and no b-roll.But these are not bodies in the woods or warehouses or the backs of cars - these are artworks and they come in two parts. True Crime at Screw Gallery is not the first time that these works were made viewable to the public. They were leaked on Reddit, Live Leak and 4Chan under the auspices of the OP having found the photographs in a storage locker bought at auction (could we make the connection to low-level TV entertainment more clear?).

Each of these posts resulted in the OP being banned from the site which is surprising considering the very real horror propagated on each of them - from the brutality of war, to car-crash victims and (in the case of the latter) hate-speech running rampant - Dunlap's seed for what resulted in a strange sort of True Crime ARG was deemed too much. Live Leak is probably the easiest site to use as an example for why (with the caveat that none of these spaces would allow for a murderer to wantonly post photos of victims, which I suppose they may have genuinely believed this could have been) these posts were so quickly removed and the accounts band, my theory being that these images (while graphic) are not gorey, bloody or grotesque. There is very little gross out value for teenagers to shock their friends with, the abject nature of the images brings them into a world of physical horror. We place ourselves, our loved ones in the positions of the fictional victims - they create a visceral spike of empathy, fear for the potential harm that can come to vulnerable people and at the same time are entirely aware of mortality as a concept, that life and living are not given.